February 17, 2023

One of the most perplexing aspects of today’s economy is the enduring strength of the labor market. The three-month average increase of 356 thousand jobs is far larger than anyone expected. The most often cited explanation is that given the extreme difficulty in hiring workers over the past two years many firms are reluctant to lay off workers today for fear they may not be able to get them back when they really need them. That is a plausible explanation, but it is different from anything that we have experienced in our economic history. There may be an even better explanation. Right now the economy remains resilient and inflation stubbornly high. Could it be that the economy is growing far more quickly than anybody expected and that firms actually need those additional workers? That scenario is not on anybody’s radar screen. But if it is correct, the Fed has a lot more work to do and interest rates will climb a lot more than is generally expected at the moment.

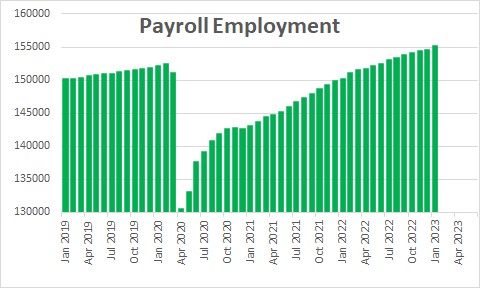

The labor market by any measure is extremely right. Payroll employment has slowed during the past year from 516 thousand jobs per month a year ago to 386 thousand per month currently. With the labor force rising by about 200 thousand per month, monthly jobs gains of 386 thousand are huge.

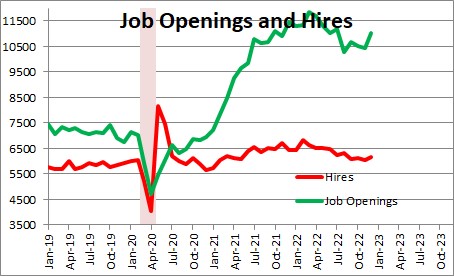

Employers simply cannot find enough bodies to hire. Job openings at 11.0 million are near a record high level.

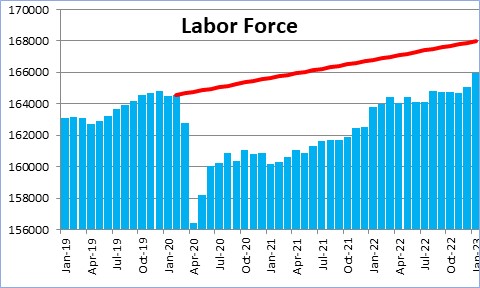

The difficultly in hiring has been caused by surprisingly slow growth in the labor force. During the pandemic and the associated lockdown, many workers chose to retire, some died from COVID, and still others dropped out for a variety of reasons. As a result, the labor force today is about 2.5 million workers smaller than it should be. No wonder firms cannot find an adequate number of workers. They simply are not available. As a result, firms bid aggressively to steal workers from others.

Against this background it is perhaps not too surprising that business leaders are choosing to hang onto workers who show up and seem reliable despite the prospect of an upcoming recession. That is almost certainly part of the story. But there may be an even more obvious explanation.

In the past couple of weeks the economic data are proving to be far stronger than anticipated and the inflation rate does not appear to be slowing quickly. For example, the employment report for January was unambiguously strong with a monthly jobs gain of 517 thousand and a 0.1% decline in the unemployment rate to a 55-year low of 3.4%. Retail sales surged by an eye-popping 3.0%. As a result, economists have been scrambling to boost their first quarter GDP growth projections from 0.5-1.0% to the 2.0-2.5% range. With GDP growth in the third quarter of 3.2%, 2.9% growth in the fourth quarter, and now 2.0-2.5% in the first quarter, the economy seems to have far more momentum than anybody expected with few signs of the long-awaited slowdown in sight. With growth steady at 2.0-3.0% it should not be a real surprise that hiring remains robust. Firms need more workers.

Meanwhile, the CPI data after its annual revision showed far less of a slowdown in inflation in the fourth quarter of 2022 than had been anticipated. Previously, in the final quarter of 2022 the core CPI had climbed at a 3.1% pace. After revision it grew at a less friendly 4.5%.

All of this suggests that the Fed has more work to do. Perhaps a lot more. Today the real funds rate is -0.7% — a 4.75% funds rate combined with a 5.4% core inflation rate. A negative real funds rate will neither significantly slow the pace of economic activity nor reduce inflation. By midyear we expect the funds rate to be 5.5% and the core CPI to slip to 4.9% which works out to a real funds rate of +0.6%. Will that be high enough to do the trick? Or might a 6.0% funds rate and a +1.1% real funds rate be required to bring about the desired result? Nobody knows. But what is important is that firms are not being irrational after all.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

The “Unrecession” … 🙂

No landing?

Has there ever been an industrialized economy that suffered a recession while at full-employment?

Hi Sidney,

I do not know of any. The way monetary policy works is that the Fed (or any central bank) starts raising interest rates. Eventually, real rates get to be significantly positive and the yield curve inverts. That sets the stage for a big drop-off in demand — and starts the labor market softening. As workers get laid off, consumer spending declines, businesses cut back on investment, and the recession sets in.

So the economy may well be a full-employment before all of this happens, but when you see payroll employment (and industrial production) decline for the first time, that is probably the month that will mark the start of the recession. Initial unemployment claims (the weekly series on layoffs) is a leading indicator. It provides a sense that employers are starting to lay off workers and bad things are soon going to happen. Payroll employment is a coincident indicator. It begins to fall when the recession is finally underway. The unemployment rate is a lagging indicator of the economy. Employers lay off some workers and work others shorter hours. It takes several months for enough employers to lay off workers that the unemployment rate starts to rise.

In short, these economies may have been at full employment until rates climb enough to bite. Then everything begins to unravel. It does not appear that we are there quite yet.

Best.

Steve