May 4, 2018

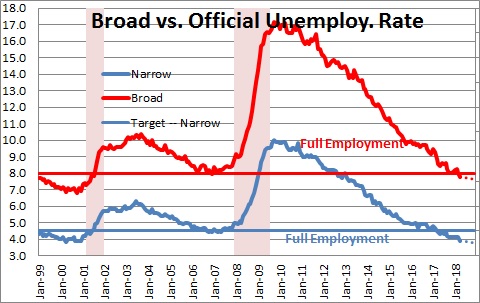

The unemployment rate declined 0.2% in April to 3.9%. That is the lowest it has been since December 2000. Economists generally believe that the full employment threshold – the rate at which everyone who wants a job has one – is about 4.5%. Surely, the economy has reached that mark. With monthly job gains continuing to exceed the average monthly increase in the labor force, the unemployment rate will continue to decline in the months ahead.

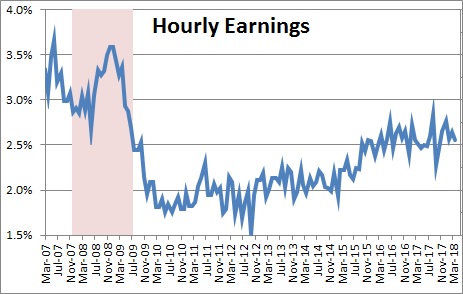

If that is true, wage pressures should be quickening. That seems to be the case. Average hourly earnings have risen 2.7% in the past year and are on a gradual upswing.

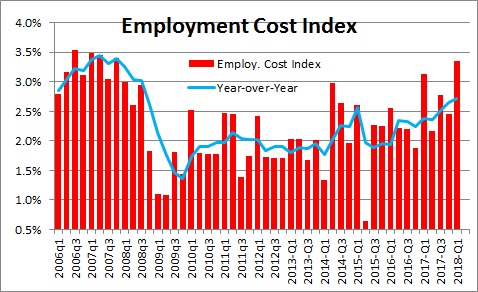

The employment cost index is a broader measure of labor costs which includes the cost of wages for both hourly and salaried workers and the cost of many benefits. It is the broadest measure of wage pressures. Like average hourly earnings, this series has risen 2.7% in the past year. That happens to be the biggest year-over-year increase in labor costs in a decade.

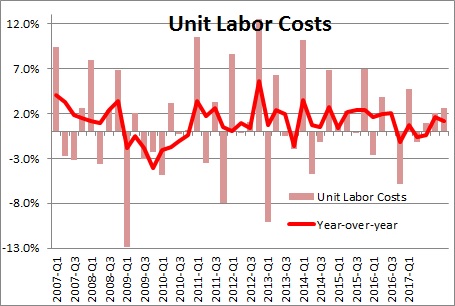

It would be logical to assume that since labor costs represent about two-thirds of a firm’s overall costs, accelerating labor costs will put upward pressure on the inflation rate. But be careful. The various measures of labor costs can be misleading. What we need to watch are “unit labor costs” which are labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity. If an employer pays its workers 3.0% higher wages because they are 3.0% more productive, there will be no reason for the employer to raise prices because he or she is getting 3.0% more output. Workers have earned their fatter paychecks. In this case “unit labor costs” are 0.0% — 3.0% higher wages exactly matched by a 3.0% increase in productivity. We recently received data on unit labor costs for the first quarter. In the past year unit labor costs have risen 1.1%, considerably less than one might expect by looking at the various measures of labor costs. That 1.1% increase in unit labor costs consisted of a 2.5% increase in compensation partially offset by a 1.3% increase in productivity. Going forward we expect compensation to increase 3.5% in 2018, productivity to increase 1.5%, which means that ULC’s for the year will increase 2.0%. This will not result in much upward pressure on the inflation rate because unit labor costs will be rising at the same 2.0% pace as the Fed’s inflation target.

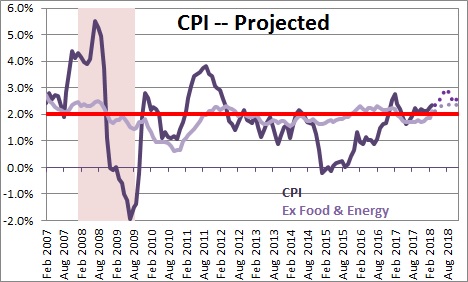

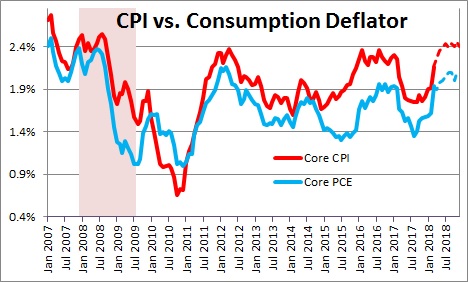

One final point, the overall CPI index is on track to increase 2.5% this year. While this is slightly faster than the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target, it is important to remember that the Fed’s specific inflation objective is not the CPI.

Rather, the Fed targets the personal consumption expenditures deflator excluding the volatile food and energy categories. This is a weighted measure of inflation which means that if, as prices rise, consumers substitute a lower priced good for a higher priced one to save money (the old substitution of margarine for butter example that many of us learned about in Econ 101) then a weighted measure of inflation will rise more slowly than the fixed-weight CPI measure because it will give greater weight to the lower-priced good. Over time the “core” personal consumption expenditures deflator tends to rise about 0.5% more slowly than the CPI. Thus, we expect the “core” PCE deflator to increase 2.0% this year which is exactly in line with the Fed’s stated 2.0% inflation target.

What all of this means is that the Fed does not have to be in hurry to raise short-term interest rates. Yes, the economy will grow more quickly this year, the unemployment rate will continue to decline, wage pressures will accelerate, and inflation will rise. But if inflation climbs at the Fed’s targeted 2.0% pace it does not have to panic. In fact, because this inflation measure has been far below target for so long the Fed will probably will be thrilled with that outcome.

Given the above, the Fed will maintain its path of gradually raising the funds rate. Whether it will raise rates two or three more times in 2018 is irrelevant. The Fed plans to gradually boost the funds rate to the 3.0% mark or a bit higher. However, the funds rate will not reach that level until the end of next year or sometime in early 2020. That is a long time down the road.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me