May 19, 2023

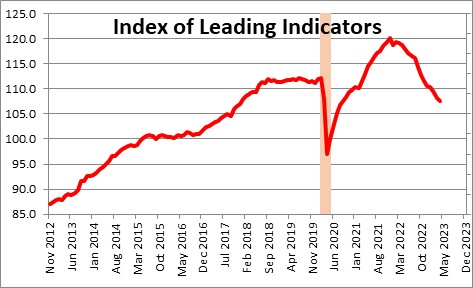

The Conference Board’s index of leading indicators (LEI) has been falling steadily since December 2021. The index anticipates turning points in the business cycle by around 10 months. Based on this steep slide the Conference Board forecasts a recession in the second half of the year. The Federal Reserve also anticipates a second half recession as do many private sector economists. But the index has been falling for 16 months and the long-anticipated recession is not yet in sight. Given that virtually every economic indicator has been distorted since the March/April 2020 recession, is it possible that economists are misreading the economic tea leaves? Could it be that the LEI is no longer an accurate barometer of future economic activity? Or could it be giving us the right signal, but raising the red flag far earlier than normal?

The index of leading indicator consists of ten components that cover a wide range of economic activity. It includes indicators from the stock market, consumer sentiment, the labor market, the housing sector, and manufacturing. Each of its ten components is itself a leading economic indicator. The idea is that the performance of all ten combined gives a better reading of future economic activity than any individual component. Historically it works fairly well but the lead times are variable. At the peak of a business cycle the lead time can be anywhere from 3 months to a year or more. At the bottom the lead time is much shorter, typically 1-3 months. And the LEI is not infallible. It does occasionally anticipate a recession that never materializes. But the index has never fallen this far for this long and been wrong.

We do not intend to review each component of the index of leading indicators, but to highlight a few that have been major contributors to the slide but may be overemphasizing the extent of economic softness that might be forthcoming.

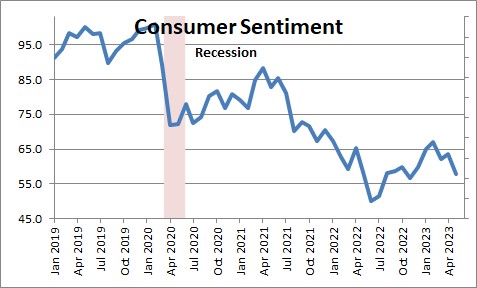

Consumer Expectations. The LEI includes the expectations component of the University of Michigan’s gauge of consumer sentiment. Sentiment today is not only lower than it was at the bottom of the 2020 recession when everyone was worried about COVID and the impact of the government-imposed shutdown, it is comparable to the lowest level reached in the so-called “Great Recession” of 2008-2009. But the current state of the economy is unlike either of those earlier periods. The worst that anybody anticipates is a “mild” recession.

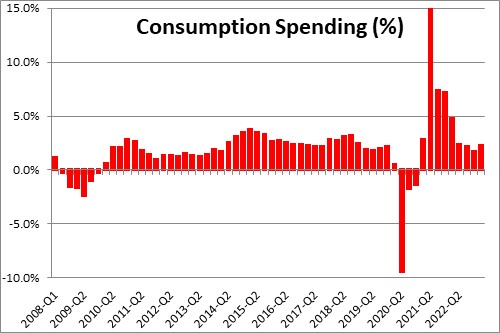

Given the drop in consumer sentiment, one would have expected consumers to curtail spending. But consumer spending has held up well. This is puzzling.

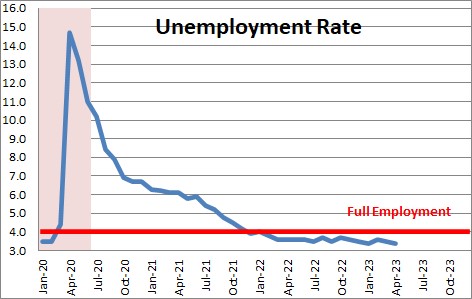

We have suggested in the past that part of the reason for this surprising outcome is that the 3.4% unemployment rate is the lowest in 50 years. If workers lose their job, they can easily find another. There is no concern that they will have their income stream interrupted, so they perhaps choose to keep spending.

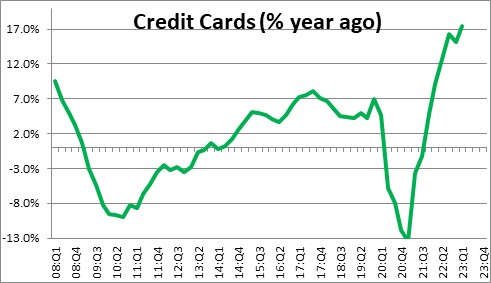

While still spending credit card debt has increased 17% in the past year. Thus, consumers are borrowing to maintain their lifestyle. That is not sustainable over the long term.

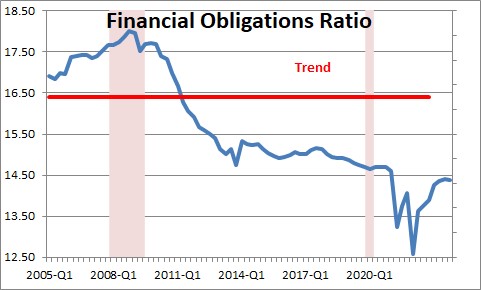

But during the recession consumers took advantage of the stimulus checks and paid down a considerable amount of debt. In the process, their monthly debt payments as a percent of income plunged to the lowest level since the 1980’s. So while the recent rapid pace of borrowing has boosted this ratio, it started at a record low level and still remains far below its historical average.

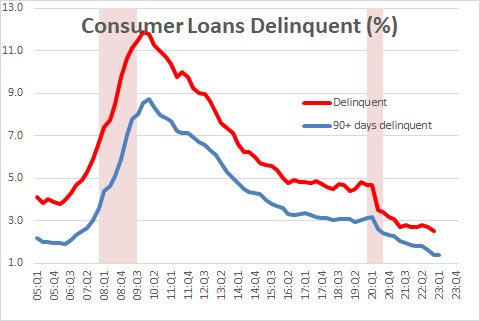

When consumer debt becomes a problem delinquency rates will rise. But delinquency rates remain at their lowest level in years. If we keep borrowing rapidly that situation will eventually change, but thus far there is no hint that we are close to the tipping point.

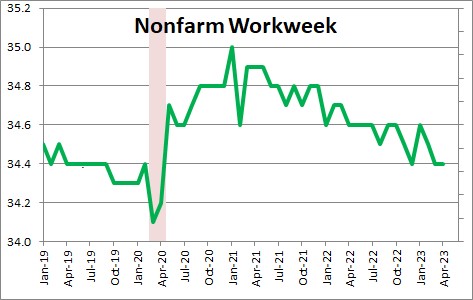

Nonfarm workweek. When the economy is growing employers need to boost output. They can either hire more workers or work existing employees longer hours. When the pace of economic activity softens they will initially shorten worker hours because they do not yet know whether the emerging weakness will be temporary or the beginning of a longer-lasting slump. If they shorten hours they can easily lengthen them if orders rebound. If the economic slump is prolonged the next step would be layoffs. Hence, the workweek is a leading indicator of changes in the labor market.

In today’s world, firms have been shortening hours steadily since the Fed began to raise rates in early 2022. Hence, they have been able to trim output without having to lay off workers. But note that after the 2020 recession, the workweek surged as demand skyrocketed once the economy reopened. At that point the workweek was abnormally long. While it has declined for the past two years, it has returned to the same level that existed prior to the weakness. Hence, is the workweek an indicator that a sustainable pace of economic activity lies ahead? Or is this a sign of emerging weakness?

The dramatic and prolonged decline in the index of leading indicators – as well as the drop in every one of its components – has convinced almost everybody that a recession will occur in the not-too-far-distant future. But consumers and business leaders are not behaving exactly like they did in the past. As a result, the LEI may be overstating both the magnitude and the timing of any upcoming economic downtown. However, the decline in the LEI is too widespread and too prolonged to be dismissed entirely. The economy is clearly slowing down, but by how much and whether a recession is in the works have yet to be determined.

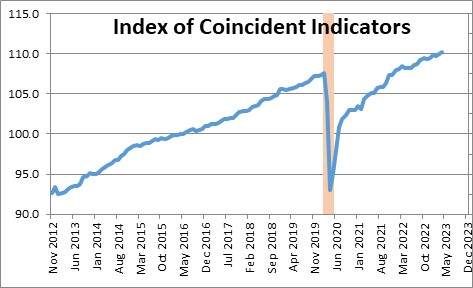

So how will we know when the recession has arrived? Easy. The Conference Board has a companion index known as the Index of Coincident Indicators. The Index of Leading Indicators tells us that a recession is coming at some point down the road. The Index of Coincident Indicators tells us when it has arrived. This index continues to climb, which means that the economy is still growing. When it turns downward sharply, the jig is up.

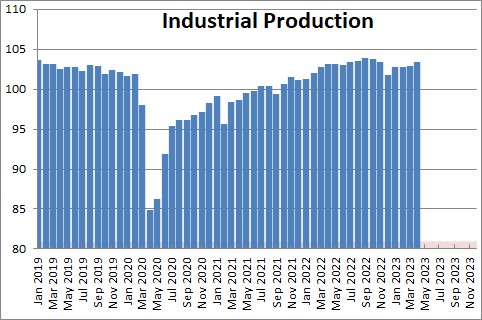

What indicators are included in the Index of Coincident Indicators? Payroll employment and industrial production are two of its three components. When they begin to turn downwards the recession will have arrived. Right now payroll employment continues to climb. In the past three months it has risen on average 211 thousand per month. Judging by the relative stability of layoffs (initial unemployment claims) payroll employment is unlikely to dip into negative territory any time soon.

Industrial production has been steady for the past year. When the recession begins this index should plunge.

The index of leading indicators appears to be signaling that a recession is coming. But given that economic behavior has changed so much in the past three years, we are skeptical of both the timing and the magnitude of the economic slump. So unlike the Fed and many private sector economists we do not expect a recession to begin in the second half of this year. It will eventually arrive, but to get there we think the Fed will need to boost the funds rate to 6.0% or so.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

When I studied economics at Duke, they used to have an economics joke:

Why do economics professors use the same test every year?

Answer: Because the answer is always changing.

Relevance: Since 2020 recession, the rules have changed so past precedents don’t necessarily fit.